Power pioneer invents new battery that’s 90% cheaper than lithium-ion

All-polymer batteries could cut manufacturing costs by 90%.

Japanese startup outfitting factory to begin mass production.

Lithium-ion batteries play a central role in the world of technology, powering everything from smartphones to smart cars, and one of the people who helped commercialize them says he has a way to cut mass production costs by 90% and significantly improve their safety.

Hideaki Horie, formerly of Nissan Motor Co., founded Tokyo-based APB Corp. in 2018 to make “all-polymer batteries” -- hence the company name. Earlier this year the company received backing from a group of Japanese firms that includes general contractor Obayashi Corp., industrial equipment manufacturer Yokogawa Electric Corp. and carbon fiber maker Teijin Ltd.

“The problem with making lithium batteries now is that it’s device manufacturing like semiconductors,” Horie said in an interview. “Our goal is to make it more like steel production.”

The making of a cell, every battery’s basic unit, is a complicated process requiring cleanroom conditions -- with airlocks to control moisture, constant air filtering and exacting precision to prevent contamination of highly reactive materials. The setup can be so expensive that a handful of top players like South Korea’s LG Chem Ltd., China’s CATL and Japan’s Panasonic Corp. spend billions of dollars to build a suitable factory.

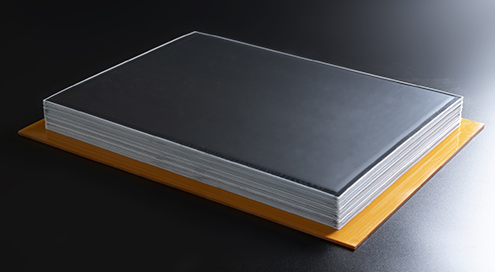

Horie’s innovation is to replace the battery’s basic components -- metal-lined electrodes and liquid electrolytes -- with a resin construction. He says this approach dramatically simplifies and speeds up manufacturing, making it as easy as “buttering toast.” It allows for 10-meter-long battery sheets that can be stacked on top of each other “like seat cushions” to increase capacity, he said. Importantly, the resin-based batteries are also resistant to catching fire when punctured.

In March, APB raised 8 billion yen ($74 million), which is tiny by the wider industry’s standards but will be enough to fully equip one factory for mass production slated to start next year. Horie estimates the funds will get his plant in central Japan to 1 gigawatt-hour capacity by 2023.

Lithium-ion batteries have come a long way since they were first commercialized almost three decades ago. They last longer, pack more power and cost 85% less than they did 10 years ago, serving as the quiet workhorse driving the growth of smartphones and tablets with ever more powerful internals. But safety remains an issue and batteries have been the cause of fires in everything from Tesla Inc.’s cars to Boeing Co.’s Dreamliner jets and Samsung Electronics Co.’s smartphones.

Hideaki HorieSource: APB Corporation

“Just from the standpoint of physics, the lithium-ion battery is the best heater humanity has ever created,” Horie said.

In a traditional battery, a puncture can create a surge measuring hundreds of amperes, several times the current of electricity delivered to an average home. Temperatures can then shoot up to 700 degrees Celsius. APB’s battery avoids such cataclysmic conditions by using a so-called bipolar design, doing away with present-day power bottlenecks and allowing the entire surface of the battery to absorb surges.

“Because of the many incidents, safety has been at the top of mind in the industry,” said Mitalee Gupta, senior analyst for energy storage at Wood Mackenzie. “This could be a breakthrough for both storage and electric vehicle applications, provided that the company is able to scale up pretty quickly.”

But the technology is not without its shortcomings. Polymers are not as conductive as metal and this could significantly impact the battery’s carrying capacity, according to Menahem Anderman, president of California-based Total Battery Consulting Inc. One drawback of the bipolar design is that cells are connected back-to-back in a series, making control of individual ones difficult, Anderman said. He also questioned whether the cost savings will be sufficient to compete with the incumbents.

“Capital is not killing the cost of a lithium-ion battery,” Anderman said. “Lithium-ion with liquid electrolyte will remain the main application for another 15 years or more. It’s not perfect and it isn’t cheap, but beyond lithium-ion is a better lithium ion.”

Horie acknowledges that APB can’t compete with battery giants who are already benefiting from economies of scale after investing billions. Instead of targeting the “red ocean” of the automotive sector, APB will first focus on stationary batteries used in buildings, offices and power plants.

That market will be worth $100 billion by 2025 worldwide, more than five times its size last year, according to estimates by Wood Mackenzie. The U.S. alone -- which together with China will be the main source of increased energy storage demand -- is likely to see a 10-fold increase to $7 billion in the period.

Horie, 63, got his start with lithium-ion batteries at their very beginning. In February 1990, early on in his Nissan career, he started the automaker’s nascent research into electric and hybrid vehicles. A few weeks later, Sony Corp. shocked the industry, which was betting on nickel-hydride technology, by announcing plans to commercialize a lithium-ion alternative. Horie says he immediately saw the promise and pushed for the two companies to combine research efforts that same year.

By 2000, however, Nissan was giving up on its battery business, having just been rescued by Renault SA. Horie had one shot at convincing his new boss Carlos Ghosn that electric vehicles were worth it. After a 28-minute presentation, a visibly excited Ghosn proclaimed Horie’s work an important investment and green-lit the project. Nissan’s Leaf would go on to become the best-selling EV for a decade.

Horie came up with the idea for the all-polymer battery while still at Nissan but wasn’t able to get institutional backing to make it real. In 2012, while doing a teaching stint at the University of Tokyo, he was approached by Sanyo Chemical Industries Ltd., known for its superabsorbent materials used in diapers. Together, the two developed the world’s first battery using a conductive gel polymer. In 2018, Horie founded APB and Sanyo Chemical became one of his early investors.

APB has already lined up its first customer, a large Japanese company whose niche and high-value-added products sell mostly overseas, Horie said. He declined to give further details and said APB plans to make the announcement as early as August.

“This will be the proof that our batteries can be mass-produced,” Horie said. “Battery makers have become assemblers. We are putting chemistry back into the lead role.”

Written by Pavel Alpeyev, with assistance by Jason Clenfield, David Stringer, and Daixin Li